House of Terror Museum: Shadows Cast in Stone

An unflinching journey through Hungary’s darkest hours, where walls remember and silence speaks

Where the Street Darkens and Memory Begins

Andrássy Avenue is a boulevard of elegance. Lined with neo-Renaissance townhouses, theaters, and embassies, it carries the air of a city once crowned an imperial jewel. But at Number 60, the mood shifts. The light dims. A black steel canopy looms overhead, its cut-out letters spelling TERROR in a silent scream that casts its shadow on the sidewalk below.

This is the House of Terror Museum—not merely a building, but an artifact of pain, remembrance, and confrontation. Once the headquarters of Hungary’s two most brutal regimes—the Arrow Cross Party and later the State Protection Authority (ÁVH)—this address is a scar carved into Budapest’s heart. It now stands not only as a museum but as a warning, an elegy, and a shrine.

A Place with Two Ghosts

From 1944 to 1945, the building housed the Arrow Cross, Hungary’s fascist militia. Inspired by Nazi ideology, they orchestrated the deportation, torture, and execution of tens of thousands—primarily Jews, Roma, and political opponents. In its basement, blood pooled on stone. The Danube ran red. The city screamed, and this building heard it all.

Then came the Soviets.

From 1945 until 1956, the building became the domain of the ÁVH, the communist secret police. Surveillance, blackmail, false accusations, and show trials became everyday tools. The same basement cells were now used by new jailers. The ideologies had changed, but the cruelty remained.

This was a house of fear. A fortress of whisper networks, interrogation rooms, and vanishing neighbors. It was not symbolic violence—it was real. And it shaped a nation’s psyche for generations.

Architecture of Anguish

When the building was reborn as the House of Terror Museum in 2002, it was not done with subtlety. The facade is framed in iron-black stone, with sharp edges and a sky-slicing awning that casts those infamous shadow letters: T-E-R-R-O-R. The name looms above the entrance like a judgment.

Inside, the museum’s architecture works like choreography. It doesn’t guide you. It pulls you. The floors creak underfoot. Hallways are narrow, walls are dark, rooms are underlit, ceilings low. It replicates the psychological weight of surveillance and confinement.

Sound design plays a crucial role. Whispers float in the air. Marching boots echo. Propaganda blares. Each step you take feels like trespass.

The Journey Through Fear

The exhibition unfolds chronologically and thematically. You start upstairs, in a bright but sterile gallery. It is the prelude—a calm before history descends.

The Arrow Cross Rooms

You enter the fascist period first: uniforms, armbands, video testimonies, Nazi correspondence. A map of Hungary glows red with the spread of hate. You see lists. Names. Orders. Deportation notices typed in cold ink.

There are interactive touchscreens, showing original documents and footage from the Arrow Cross era. Victims' faces stare back—boys, teachers, rabbis, girls. One chamber re-creates the office of the Arrow Cross commander. The desk is real. So is the ledger.

The Soviet Shadow

As the war ends, you descend into another nightmare. A red star greets you. Lenin’s face looms. The language shifts—but the mechanisms stay the same.

A corridor titled “The Everyday of Fear” reveals how the ÁVH infiltrated lives. Letters were opened. Telephones tapped. Children were used to spy on parents. The line between informer and informed blurred until trust itself became contraband.

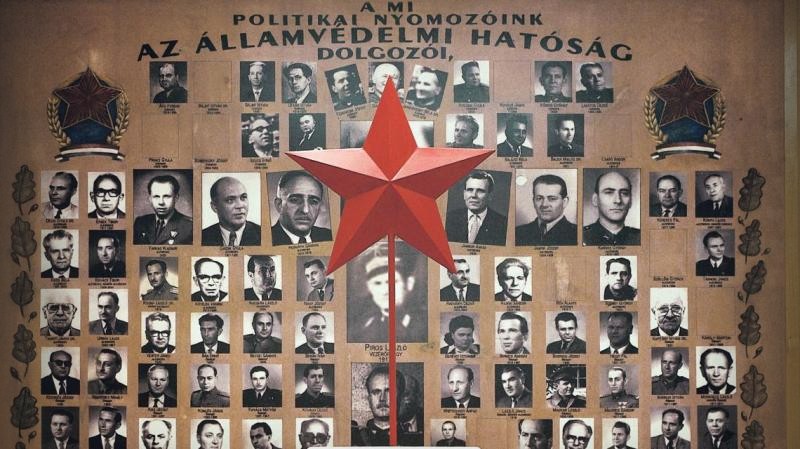

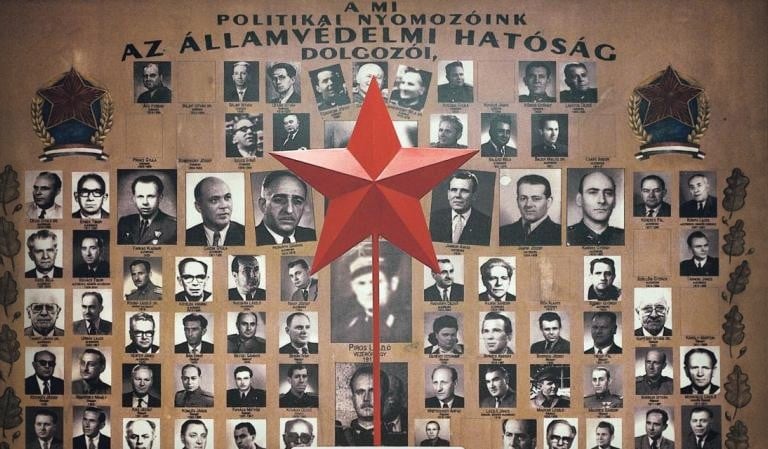

An entire wall is covered in Mugshots of the Vanished—a grid of black-and-white faces, each arrested, tortured, or executed. The uniformity of their gazes is haunting. It’s not a wall of criminals. It’s a gallery of stolen lives.

Interrogation and Punishment

The tone turns colder. You walk into the Cellar. Dim lights. Rough stone. This is not a simulation. These are the real rooms. The detention cells, the solitary confinement box, the interrogation chair. Metal shackles are still bolted into the walls.

You feel it: not just the history, but the weight of it. The claustrophobia. The stale air. The silence that screams louder than voices.

In one chamber, a screen plays a looping video of survivors describing what it was like to be imprisoned here. The language is quiet. The emotion is not. It crawls under your skin.

Artifacts of Complicity

One room displays everyday objects—not just instruments of oppression, but instruments of indifference. Communist uniforms, ration cards, schoolbooks teaching Stalinist ideology. The “normalcy” of oppression is more chilling than its violence.

A poignant corner is devoted to forced labor camps, where tens of thousands were sent for crimes such as listening to Western radio or making a joke about the regime. Postcards from prisoners are displayed, written in code, sent to families who never saw them again.

You exit through a corridor lined with portraits of perpetrators. Not to demonize. To identify. These were Hungarians. Bureaucrats, teachers, neighbors. The museum forces confrontation—not just with the past, but with complicity.

The Final Room: Light and Names

The last space is spare, almost sacred. A room of light. Its walls bear the names of all known victims of both regimes. Thousands upon thousands. You can scroll digitally through testimonies, photos, and fates. Some are detailed. Others say only: “Disappeared. Date unknown.”

A single wreath sits in the center of the room. No guards. No glass. Just the enormity of what remains.

Memory as Resistance

The House of Terror Museum is not simply a documentation of historical fact. It is a psychological map, charting the mechanics of fear, obedience, and erasure. It asks not just what happened, but how it happened—how ideologies can twist love into hate, neighbors into traitors, homes into prisons.

In Hungary, memory is contested terrain. The museum, curated under the direction of Mária Schmidt, has not escaped criticism. Some argue it emphasizes communist atrocities more than fascist ones, and that its narrative frames Hungary exclusively as a victim of foreign regimes rather than acknowledging internal collaboration.

But even in its controversies, the House of Terror is fulfilling its purpose—it is keeping the conversation alive. History is not a monument. It is a wound that speaks, and here, it speaks in every corridor.

Education and Reflection

The museum is deeply invested in education, especially for young Hungarians. School groups arrive daily, led by guides trained not just to explain, but to invite reflection. There are tailored tours, printable materials, and thematic lessons in both Hungarian and English.

In addition, the museum produces books, documentary films, conferences, and international symposia, bringing together historians, survivors, and citizens to explore the echoes of totalitarianism across Europe.

Its library is open to researchers, and it collaborates with organizations across Germany, Israel, and the former Eastern Bloc to build a transnational memory. The goal is not to fix the past, but to understand it—and thereby, guard the present.

Visiting Information

Address

House of Terror Museum

Andrássy út 60

1062 Budapest, Hungary

The museum is centrally located on the grand Andrássy Avenue, a 5-minute walk from Oktogon and easily accessible via Metro Line 1 (Vörösmarty utca station).

Opening Hours

Tuesday to Sunday: 10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

Closed on Mondays

Last admission: 5:30 PM

Allow at least 90 minutes for your visit. Audio guides are available in multiple languages, including English, German, French, and Russian.

Ticket Prices

Adults: 4,000 HUF (~$11 USD)

Students (EU/EEA, 6–26): 2,000 HUF (~$5.50 USD)

Seniors (EU/EEA, 62–70): 2,000 HUF

Children under 6: Free

Group ticket (20+ people): 3,000 HUF per person

Group reduced (students/seniors): 1,500 HUF per person

Note: Discounts apply only to EU and EEA citizens. Tickets can be bought at the door or online.

Accessibility

The museum is wheelchair accessible via a side entrance.

An elevator serves all floors.

Seating areas are available throughout the building.

Audio guides and printed materials are designed for inclusive learning.

For assistance or special needs, email or call ahead.

Contact Information

Phone: +36 1 374 2600

Email: info@terrorhaza.hu

Official Website and Social Media

Website: https://www.terrorhaza.hu/en

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/terrorhazamuzeum