Become HUNGARIAN

SPEAK LIKE A REAL NATIVE

AUTHENTIC HUNGARIAN LIVING

From its founding in 896 AD by the Magyar tribes to its golden age as part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Hungary has played a pivotal role in European history. Its rich cultural tapestry reflects influences from Roman, Ottoman, and Habsburg rule, blended with deeply rooted Magyar traditions. With its stunning architectural heritage, from medieval castles to iconic thermal baths, Hungary offers a timeless journey through its dynamic and enduring cultural legacy.

After the fall of communism in 1989, Hungary underwent a remarkable transformation. The nation embraced political and economic reforms, joining the European Union in 2004 and positioning itself as a dynamic player in Central Europe. Its thriving arts scene, expanding tourism industry, and focus on education and technology showcase a country that honors its past while forging a bright future. Today, Hungary is a bridge between East and West, celebrated for its unique language, cuisine, and spirit of resilience.

We have created a selection of words and expressions that you won't find in any textbook or course, to make you become a real native by helping you understand Hungarian words that carry a deeper cultural meaning as well as expand your knowledge of the country and its history.

Speak and think like a real Hungarian!

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Hungarian, we recommend that you download the Complete Hungarian Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't find in any other textbook so you can amaze your Hungarian friends thanks to your knowledge of their country and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get hours of Podcasts to Practice your Hungarian listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Hungarian today!

CHIMNEY CAKE

Kürtőskalács (chimney cake) is one of Hungary’s most iconic and beloved pastries, a sweet, spiral-shaped treat that has moved from traditional village fairs to the international street food scene without losing any of its rustic charm or cultural significance. Baked over open coals or electric rotisseries, coated in caramelized sugar and rolled in toppings like fahéj (cinnamon), dió (walnut), or kókuszreszelék (grated coconut), kürtőskalács is not just a dessert—it is a multisensory experience. The scent alone, warm and toasty with hints of vanilla and smoke, is enough to draw people to market stalls across Hungary, where the pastry’s golden crust crackles invitingly as it’s pulled fresh from the spit.

The name kürtőskalács comes from kürtő (chimney), reflecting both the cylindrical shape of the finished pastry and the smoky method of preparation that was once common in Transylvanian wood-fired ovens. Though strongly associated today with Hungary proper, the dessert actually has its roots in the székely (Szekler) communities of eastern Transylvania, where it has been baked for centuries as part of festive occasions, especially esküvők (weddings), búcsúk (pilgrimages), and szüreti bálok (harvest balls). Traditionally, the dough is yeast-raised, enriched with butter and eggs, then stretched into a long rope, wound around a wooden cylinder, and slowly rotated above embers while being basted with cukorszirup (sugar syrup). As the sugar melts and caramelizes, it forms a delicate shell that crackles under your fingers and melts on your tongue.

The preparation of kürtőskalács is almost theatrical, often performed in full view of customers, adding to its allure. Watching the dough twirl and swell, hearing the hiss of sugar hitting the coals, and catching the sweet scent of toasted glaze in the air turns a simple snack into a kind of performance. At vásárok (fairs) and karácsonyi vásárok (Christmas markets), it’s not uncommon to see people lined up, clutching steaming cones of the pastry with a childlike smile. Whether eaten plain or customized with csokoládé (chocolate), mák (poppy seeds), or mandula (almonds), kürtőskalács delivers more than sweetness—it offers a taste of nostalgia, celebration, and Hungarian ingenuity.

In recent years, kürtőskalács has undergone a renaissance, appearing not only in its classic form but also as a vehicle for modern culinary creativity. Some bakeries now serve it filled with fagylalt (ice cream), whipped cream, or even savory ingredients like cheese and ham. International food festivals have embraced it as Hungary’s answer to the donut or waffle cone, and Hungarian expatriates have brought the recipe to global cities where kürtőskalács trucks and stalls now flourish. Meanwhile, back home, organizations like the Kürtőskalács Fesztivál (Chimney Cake Festival) celebrate the pastry’s rich history and versatility, offering competitions, tastings, and masterclasses that keep the tradition both alive and evolving.

WATER POLO

In Hungary, vízilabda (water polo) is not just a sport—it is a national obsession, a source of pride, and a symbol of Hungarian excellence on the world stage. For over a century, Hungary has dominated this physically demanding aquatic game, producing generations of elite athletes and unforgettable victories.

Played with ferocity, intelligence, and astonishing endurance, vízilabda holds a special place in the Hungarian soul, earning the country an almost mythic reputation as the sport's greatest powerhouse. From packed stadiums to humble uszodák (swimming pools), the sport pulses through the veins of the nation. The roots of Hungarian water polo stretch back to the early 20th century, when the game began gaining popularity in the fürdőkultúra (bathing culture) of Budapest and other spa towns. With the rise of organized clubs and dedicated coaches, Hungarian vízilabdázók (water polo players) quickly ascended in international rankings. By the time the Olympic Games resumed after World War I, Hungary was already emerging as a dominant force.

The country's golden era began in the 1930s and continued into the 2000s, with multiple Olympic gold medals, World Championships, and European titles adding to an already glittering legacy. Names like Kásás Tamás, Benedek Tibor, and Biros Péter are spoken with reverence, not only for their medal counts but for their strategic brilliance and ability to perform under intense pressure. The 1956 Melbourne-i olimpia (Melbourne Olympics) is especially etched into national memory for the infamous vérfürdő mérkőzés (bloodbath match) against the Soviet Union, where political tension erupted in the pool just weeks after the suppression of the Hungarian Revolution. The Hungarian team’s 4–0 victory that day became a symbolic act of resistance, and the image of a bloodied Hungarian player emerging defiantly from the water became iconic. Today, the tradition of excellence continues through youth development programs, state support, and a deeply embedded sportkultúra (sports culture).

Training in Hungary begins young, often in vízilabda utánpótlás (water polo youth development) programs that emphasize swimming technique, ball control, and tactical acumen. Matches at the OB I (Hungarian National Championship) are fiercely contested, drawing loyal fans and showcasing the deep pool of talent that keeps Hungary at the top of the international game. Whether it’s in the ancient baths of Budapest or in modern aquatic centers, the love for vízilabda runs deep. It combines national pride with the values of discipline, teamwork, and strategy—traits that resonate powerfully in Hungarian identity. With every throw, block, and goal, vízilabda continues to embody Hungary’s spirit: relentless, skillful, and always ready to rise to the occasion.

BUSO CARNIVAL

The Busójárás (Busó Carnival) in Mohács is one of the most extraordinary and atmospheric traditions in Hungary, blending pagan ritual, historical memory, and vibrant folk celebration. Held every year during farsang (carnival season), usually in late February or early March before húsvét (Easter), the event features hundreds of masked busók (Busó men) parading through the streets in horned wooden masks and thick bunda (sheepskin cloaks), creating an unforgettable visual and auditory spectacle. Their purpose is both symbolic and theatrical: to chase away the cold and darkness of winter and to usher in the renewal of spring. Accompanied by the rhythmic thumping of kolomp (cowbells), the roar of chainsaws turned instruments, the guttural laughter of the costumed figures, and the beat of dobszó (drumming), the air becomes charged with ancient energy. According to legend, the custom originates from the time of Ottoman occupation, when the locals of Mohács—mainly ethnic šokci (Šokci Croats)—donned frightening disguises and masks to scare away the Turkish invaders. Whether myth or truth, the monda (legend) adds a powerful layer of historical resistance and community pride to the celebration.

The masks themselves are carefully hand-carved from fűzfa (willow wood) and painted with fearsome expressions, often with exaggerated noses, large teeth, and fiery red eyes. These are paired with heavy cloaks made of sheep’s wool and a variety of accessories including favilla (wooden clappers), kereplő (ratchets), and in some cases, even flaming torches. One of the highlights of the event is téltemetés (winter burial), when a coffin representing winter is set aflame on the banks of the Duna (Danube), symbolically putting an end to the cold season. The főtéren (main square), crowds gather to watch the busók dance, drink pálinka (fruit brandy), eat fánk (doughnuts), and share in the mulatság (festivity) that stretches deep into the night. Children join as kisbusók (little Busós), keeping the tradition alive with innocent mischief, while women in traditional népviselet (folk costume) serve food and sing old songs. The entire town becomes a living folk theatre, with roles passed down through generations, and preparation beginning months in advance.

Recognized as a UNESCO szellemi kulturális örökség (intangible cultural heritage), the Busójárás is more than entertainment—it’s an affirmation of cultural identity, a collective catharsis, and a celebration of life's resilience. In a modern world often disconnected from seasonal rhythms and ancestral memory, the Busó Carnival stands as a powerful reminder of Hungary's enduring link to its néphagyomány (folk tradition), where myth, nature, and human spirit converge in spectacular form.

PAPRIKA

Paprika is far more than a spice in Hungary—it is a national treasure, a culinary identity, and a vibrant symbol of tradition that colors not just the cuisine but the very language and spirit of the country. Whether in powdered form, fresh, smoked, sweet, or fiery hot, paprika infuses countless Hungarian dishes with its unmistakable flavor and brilliant red hue. Found in every pantry, every leves (soup), pörkölt (stew), and töltött paprika (stuffed pepper), this humble pepper powder is a constant presence at the Hungarian table, anchoring meals in warmth, history, and the unmistakable magyar ízvilág (Hungarian flavor world).

Although paprika comes originally from the Americas, it found its spiritual home in Hungary sometime in the 16th century, following the Ottoman occupation. Initially grown as an ornamental plant or folk remedy, it wasn't until the 18th and 19th centuries that Hungarians began drying and grinding the peppers into the spice we now know as őrölt paprika (ground paprika). The fertile Alföld (Great Hungarian Plain), especially regions around Kalocsa and Szeged, proved perfect for cultivating the ideal variety—one with deep flavor, brilliant color, and a delicate balance between sweetness and heat. These two cities soon became the heartlands of paprika production, and their names are still synonymous with the highest quality paprika in the world.

There are several types of Hungarian paprika, ranging from édes (sweet) and csípős (spicy) to füstölt (smoked) and különleges (special quality), each with its own aroma and use. The most common is édesnemes, a noble sweet variety that imparts a mild flavor and vibrant red color—perfect for stews like gulyás (goulash), paprikás csirke (paprika chicken), and halászlé (fisherman’s soup). The smoky variety adds depth to meat dishes and sausages, while hot paprika enlivens sauces and pickles with a pleasant burn. Each form is handled with care, often pörkölve (lightly roasted) in oil at the beginning of a dish to release its essential oils and deepen its character.

Paprika is not only a seasoning—it is a foundation of magyar gasztronómia (Hungarian gastronomy). Cooking with it is an art form passed through generations. Grandmothers instruct children when to stir, when to add water, when the color is just right. It is also a point of pride. The iconic red tins with golden lettering that hold Szegedi paprika or Kalocsai paprika are proudly displayed in homes and gifted abroad as tokens of Hungarian heritage. Entire festivals, such as the Paprikafesztivál in Kalocsa, celebrate the harvest, with performances, parades, and tastings centered around this essential spice.

Beyond the kitchen, paprika appears in hímzett motívumok (embroidered motifs), tourism campaigns, and even Hungarian idioms. To “add paprika to something” means to make it more exciting or spicy, a metaphor for flavoring life itself. It appears on postage stamps, in museum exhibits, and in the red dust that sometimes coats the hands of butchers making paprikás kolbász (paprika sausage). For many, it is a direct link to the land, the kert (garden), and the painstaking work of growing, drying, stringing, and grinding—a labor of love that produces the red gold of Hungary.

RUBIK'S CUBE

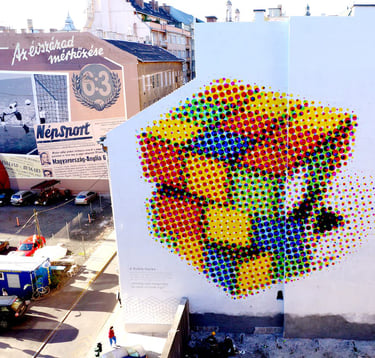

Rubik-kocka (Rubik's Cube) is arguably Hungary’s most iconic invention of the 20th century—a deceptively simple yet endlessly complex puzzle that has captivated millions around the world and cemented its place as a global symbol of logic, perseverance, and intellectual curiosity. Invented in 1974 by Hungarian architect and professor Rubik Ernő, the Rubik-kocka began as a teaching tool to explain three-dimensional geometry to his students, but it quickly transformed into an international phenomenon. With its six colorful faces, each consisting of nine smaller squares, the cube presents a challenge that is easy to grasp yet maddeningly difficult to master: return all six sides to their uniform color after a few twists scramble them into chaos.

The magic of the Rubik-kocka lies in its perfect blend of mechanical elegance and mathematical depth. Its 3x3 structure contains over 43 trillió lehetséges kombináció (43 trillion possible combinations), and yet it can be solved, in theory, in just 20 lépés (20 moves)—a number known among enthusiasts as God’s Number. This balance between staggering possibility and underlying solvability is what has made the Rubik-kocka an enduring object of fascination for both casual players and serious speedcuberek (speedcubers). Over the decades, the cube has inspired a competitive global subculture complete with world championships, algorithmic notations, and astonishing records—some megoldások (solutions) achieved in under 4 seconds.

But the cultural impact of the Rubik-kocka extends well beyond competitions. In Hungary, it stands as a symbol of magyar találékonyság (Hungarian ingenuity)—a testament to a long national tradition of problem solving, creativity, and scientific innovation. Rubik Ernő himself was a soft-spoken academic who, like many Hungarian thinkers, thrived in the margins between disciplines: art and science, form and function, education and entertainment. When his cube was first mass-produced in Hungary under the name Bűvös kocka (Magic Cube), it became a popular local toy, but it was its 1980 international release under the name Rubik’s Cube that unleashed a global craze, with millions sold within a year.

In Hungary, the cube is more than just a nostalgic toy or intellectual exercise—it is woven into educational and cultural life. Schools use it to teach spatial reasoning, logic, and patience. Kiállítások (exhibitions) and emlékhelyek (memorials) celebrate Rubik’s legacy, while artists and designers reinterpret the cube as a metaphor for human complexity and multidimensional identity. It has appeared in literature, films, fashion, and public installations, and continues to evolve through augmented reality and digital forms. Hungarian museums even dedicate entire sections to the cube’s history, showcasing rare prototypes, early packaging, and interactive solving tables.

HOT SPRINGS

Hungary is often called the land of gyógyvizek (medicinal waters), and for good reason—its geological foundation is rich in thermal activity, providing an extraordinary abundance of termálforrások (thermal springs) that bubble to the surface throughout the country. These natural melegvízű források (hot water springs) have been central to Hungarian life for centuries, used not only for relaxation but also for healing and community rituals. In cities and villages alike, the presence of fürdők (baths) has shaped social customs, urban planning, and even medical practice. Nowhere is this more visible than in Budapest, often referred to as the fürdőváros (city of baths), where grand architectural marvels like Széchenyi Fürdő and Gellért Fürdő draw locals and tourists alike into steaming pools of mineral-rich water. These baths are often divided into medencék (pools) of varying temperatures, each said to offer specific health benefits depending on the mineral content and warmth of the water. The most common minerals found include kén (sulphur), kalcium (calcium), and magnézium (magnesium), believed to assist in treating ailments such as arthritis, skin conditions, and joint pain.

The tradition of gyógyfürdőzés (bathing in medicinal water) dates back to Roman times, but it was during the török uralom (Ottoman occupation) in the 16th and 17th centuries that the culture of communal thermal bathing flourished. The Turks built elegant domed bathhouses, many of which—like Király Fürdő or Rudas Fürdő—still operate today, preserving their exotic ambiance and unique structure. These törökfürdők (Turkish baths) combine hot pools with gőzkamrák (steam rooms) and hideg merülők (cold plunge pools), offering a full-body experience that soothes, invigorates, and heals. In addition to their historical and therapeutic value, hot springs have also become vital components of the modern Hungarian wellness turizmus (wellness tourism), attracting visitors seeking both leisure and recovery. Towns like Hévíz, home to Europe’s largest natural thermal lake (Hévízi-tó), are internationally known for their gyógyászat (medical spa treatments) and iszappakolás (mud therapy), often recommended by doctors and covered by health insurance.

Hungarians don’t just visit these places—they incorporate fürdőélet (bath life) into their weekly routine. Elderly locals gather for games of chess in the water, children splash around in the élménymedencék (adventure pools), and couples unwind under thermal waterfalls. For many, it is not just a place to heal the body, but to soothe the mind, share stories, and maintain social bonds. The gyógyvíz kultúra (medicinal water culture) of Hungary remains a living, breathing tradition—a perfect convergence of nature, heritage, and well-being that continues to define the country’s identity from beneath the surface.

PALINKA

Pálinka (fruit brandy) is far more than just a strong alcoholic drink in Hungary—it is a national symbol, a cultural ritual, and a handcrafted expression of the land itself. Distilled from ripe Hungarian fruit—szilva (plum), körte (pear), barack (apricot), meggy (sour cherry), or alma (apple)—pálinka has been cherished for centuries as a medicinal tonic, a celebratory toast, and a marker of hospitality. To offer a guest a glass of pálinka is not merely a courtesy—it is an act of pride and kinship, an invitation into the Hungarian soul through the sharp clarity of a crystal-clear spirit.

The origins of pálinka stretch back to the Middle Ages, with the earliest mentions dating from the 14th century under the name "aqua vitae reginae Hungariae" (the queen of Hungary’s water of life), a herbal brandy made for medicinal use. Over time, as distillation techniques advanced and fruit agriculture flourished across regions like Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg, Bács-Kiskun, and Vas megye, pálinka became a drink of the people—homemade in villages, carefully aged in glass or ceramic, and shared in both sorrow and celebration. Whether consumed before reggeli (breakfast) as a pick-me-up or raised in a heartfelt egészségedre (to your health) toast at weddings, pálinka is always present where life happens.

Unlike generic fruit spirits found elsewhere, true pálinka is protected under European Union PDO regulation (Protected Designation of Origin), which states that only fruit brandy produced and bottled in Hungary (or specific regions of Austria) using Hungarian fruit and traditional methods can bear the name. The best pálinka is made via kisüsti (small-pot still) distillation—a slow, double distillation in copper stills that preserves the volatile esters and fruit aromas—or oszlopos (column still) distillation for cleaner, lighter flavors. No sugar, flavorings, or additives are allowed, making pálinka a true expression of terroir and craftsmanship.

What sets great pálinka apart is its balance of strength and aroma. With alcohol content usually around 40–50%, it is potent, but the best examples are smooth and fragrant, offering the nose a burst of gyümölcsillat (fruit bouquet) before the palate feels the fire. A well-made barackpálinka (apricot brandy) from Kecskemét can deliver floral notes as complex as any fine cognac, while a good szilvapálinka (plum brandy) from Szatmár can unfold layers of earthiness, sweetness, and spice. Each variety speaks of its region, its season, and the skill of the főzőmester (distiller).

In rural Hungary, the art of házi pálinkafőzés (homemade brandy-making) is a cherished tradition, passed from one generation to the next. Though recent regulations have made home distillation more restricted, many families still pride themselves on producing their own vintage, stored in dark cellars and brought out for ünnepek (holidays), disznóvágás (pig slaughter feasts), or the arrival of guests. There is also a growing network of pálinkafőzdék (craft distilleries) that are raising the bar, producing premium érlelt pálinkák (aged brandies) in oak casks and experimenting with single-varietal fruit selections and házasítások (blends).

Today, pálinka is enjoying a renaissance, both in Hungary and abroad. Tasting festivals like the Pálinkafesztivál in Budapest, museum exhibits, and tourism trails dedicated to pálinka production have elevated the drink from rustic heritage to refined connoisseurship. Mixologists are crafting modern cocktails around its complex flavors, while sommeliers pair it with desserts, cheeses, and charcuterie. Despite its elevated status, pálinka has never lost its earthy charm or its cultural heart: it remains a drink of encounter, emotion, and elemental joy.

In every drop of pálinka lives a piece of the Hungarian orchard, distilled into memory and warmth. To sip it is to taste the sunlight on apricots, the frost on plums, the labor of the harvest, and the generosity of the table. It is the drink of grandparents and grandchildren, of peasants and presidents. It is Hungary in a glass.

EASTER

In Hungary, Húsvét (Easter) is more than a Christian holiday—it is a vibrant blend of religious observance, folk ritual, and seasonal celebration that brings centuries-old customs into full bloom. While nagypéntek (Good Friday) and húsvétvasárnap (Easter Sunday) are marked by church services, candlelight, and quiet reflection on the feltámadás (resurrection), the following day, húsvéthétfő (Easter Monday), transforms villages and cities into lively stages of cultural performance. The most iconic of these traditions is locsolkodás (sprinkling), where boys visit girls to sprinkle them with water or perfume, recite locsolóversek (sprinkling poems), and in return receive hand-painted hímes tojás (decorated eggs), chocolate, or in rural areas, shots of pálinka (fruit brandy). This practice, rooted in ancient fertility rites and the symbolism of spring renewal, is still performed with cheerful formality or playful mischief, depending on the age and setting. Men often arrive in groups, sometimes wearing traditional népviselet (folk costumes), carrying old-fashioned szódásüveg (seltzer bottles) or perfume sprayers, and the ritual becomes a performance, both flirtatious and humorous, passed down like an oral poem.

Preparations for Húsvét begin during nagyböjt (Lent), a forty-day period of fasting and reflection that culminates in the rich, symbolic meals of Easter. Hungarian families prepare sonka (smoked ham), tojás (eggs), kalács (braided sweet bread), and torma (horseradish), all carefully arranged on festive tables often accompanied by piros tojás (red-dyed eggs), symbolizing life and rebirth. In many villages, a basket of these items is brought to church for the ételszentelés (food blessing), an intimate ritual where sacred meets the domestic. Children receive csokitojás (chocolate eggs) and nyuszi ajándékok (gifts from the Easter bunny), a modern layer added to ancient tradition. Yet even with commercial additions, the soul of Húsvét remains deeply tied to Hungarian néphagyomány (folk tradition). In regions like Palócföld or Kalotaszeg, large-scale reenactments of locsolás are organized, featuring singing, dancing, and néptánc (folk dance), drawing tourists and media attention alike.

Despite modernization, the core values of Easter in Hungary—renewal, purification, and joyful rebirth—continue to resonate. Whether through the icy splash of a garden hose, the aroma of freshly baked kalács, or the gentle rhythm of an Easter poem whispered over a crimson egg, Húsvét connects the Hungarian spirit with its roots. It is a time when laughter and reverence coexist, when the arrival of spring is not only felt in the budding trees but in the laughter of generations preserving something uniquely theirs.

RUIN PUBS

In the heart of Budapest’s once-abandoned belső kerületek (inner districts), a cultural revolution began to take shape in the early 2000s with the birth of romkocsmák (ruin bars)—a uniquely Hungarian phenomenon that transformed decaying buildings into vibrant hubs of creativity, community, and counterculture. These bars are typically found in the VII. kerület (7th district), particularly in the old Jewish Quarter, where crumbling bérházak (tenement buildings) and forgotten courtyards once stood as symbols of post-socialist neglect. Rather than renovate them conventionally, artists and entrepreneurs embraced the decay, filling the spaces with mismatched bútorok (furniture), salvaged lomok (junk treasures), and eclectic décor that turned disrepair into artistic statement. The result was a surreal, immersive environment where peeling plaster, ivy-covered walls, and flickering fairy lights created an atmosphere both nostalgic and defiantly modern.

The original and still most iconic of these bars is Szimpla Kert, opened in 2002, which set the tone for what a romkocsma could be: part bar, part gallery, part community center. It was a place where you could sip fröccs (wine spritzer) in a bathtub repurposed as a sofa, watch an avant-garde film projected onto a cracked wall, or listen to a zenekar (band) playing live music in a graffiti-covered garden. Other bars like Instant, Fogasház, and Ellátó Kert followed suit, each offering its own interpretation of the genre—some leaning into elektronikus zene (electronic music), others hosting irodalmi estek (literary evenings), jógaórák (yoga classes), or even bringás boltok (bike shops). The underlying ethos of all these places is accessibility and spontaneity; no polished aesthetics or velvet ropes, just a shared love of atmosphere, music, and social connection.

What makes romkocsmák uniquely Hungarian is how they reflect the country’s post-communist identity. Emerging from the ruins—both literal and metaphorical—of a bygone era, they embody a generation’s desire to reclaim public space and infuse it with life, art, and resistance. They are democratic in spirit, chaotic by design, and deeply rooted in budapesti életérzés (the Budapest feeling), where beauty lies not in perfection but in layers, textures, and contradictions. Tourists may flock to them now, but their core remains tied to the city’s fiatal művészközösség (young artist community), who still use these spaces to experiment, perform, and provoke. Even as some romkocsmák are commercialized or shut down due to gentrification, new ones emerge in more hidden corners, often under threat but always resilient.

In a city defined by imperial grandeur and turbulent history, romkocsmák offer a different kind of monument—one made not of marble but of mood, memory, and music. They are Budapest’s living rooms, its attics and basements of collective imagination, where the past meets the present in a drink-stained, candle-lit embrace.

TOKAJ WINE

Tokaji bor (Tokaj wine) holds an almost mythical status in Hungary’s cultural and historical imagination—a golden elixir celebrated in royal courts, poetry, and tradition. Grown in the Tokaji borvidék (Tokaj wine region), nestled at the foothills of the Zempléni-hegység (Zemplén Mountains), this legendary wine is more than just a drink—it is a symbol of national pride, craftsmanship, and centuries of vinicultural mastery. The region itself was designated the world’s first official zárt borvidék (closed wine region) by royal decree in 1737, long before Bordeaux or Champagne gained similar protection, underscoring Tokaj’s centrality to both Hungarian identity and global wine heritage. Its volcanic soil, unique microclimate, and morning köd (fog) from the nearby rivers Tisza and Bodrog create the perfect conditions for the development of botritisz (noble rot), the key to producing its most famous treasure: aszú.

Tokaji aszú (Tokaj aszú wine) is crafted from hand-selected, shriveled aszúszemek (aszú grapes), painstakingly picked berry by berry, and blended into alapbor (base wine), often made from varieties like furmint, hárslevelű, or sárgamuskotály (muscat blanc). The result is a golden, often amber nectar, sweet yet structured, with notes of barack (apricot), méz (honey), narancshéj (orange peel), and dió (walnut). Its complexity deepens with age, and bottles are often stored in pincék (cellars) carved into volcanic rock, where the constant temperature and high humidity ensure perfect maturation. The most prized versions are labeled by puttonyszám (number of puttonyos), a traditional measurement of sweetness and intensity—ranging from 3 to 6 or even the ultra-rare eszencia, a syrup-like wine made entirely from the free-run juice of the botrytised grapes.

Tokaji wine has long held a prestigious position in European courts and literature. It was called the “borok királya, királyok bora” (wine of kings, king of wines) by Louis XIV, and was beloved by Russian tsars, Austrian emperors, and even Polish nobles who transported it via the famous Tokaji borút (Tokaj wine route). Hungarian poets such as Vörösmarty and Petőfi immortalized Tokaj in verse, associating it with freedom, sensuality, and national identity. The wine was also exported through the Hegyalja (Uplands) into Central Europe, cementing its place as a regional luxury good. In the 20th century, despite the disruptions of war, communism, and collectivization, Tokaj’s legacy endured, and its vineyards were gradually revitalized after 1990, with both Hungarian and international investors restoring historic estates and traditional methods.

Today, Tokaji bor is experiencing a renaissance—not just in its legendary sweet wines but also in száraz furmint (dry Furmint), a crisp, mineral-driven white that has gained recognition on global wine lists. Modern cellars now coexist with centuries-old hordók (barrels), and young borászok (winemakers) experiment with bold expressions while honoring time-honored techniques. Wine festivals, like the Tokaji Szüreti Napok (Tokaj Harvest Days), bring visitors to taste, celebrate, and walk through golden vineyards where history grows in every cluster. To drink Tokaji is to savor the very soul of Hungary—sunlight, struggle, poetry, and perseverance distilled into a single glass.

LAKE BALATON

Balaton—often called the "Hungarian Sea"—is the largest freshwater lake in Central Europe and a beloved cultural and natural treasure that embodies the very essence of Hungarian summer. Stretching over 77 kilometers in length and shimmering with a milky turquoise hue, Balaton is not merely a geographical feature—it is a national symbol, a seasonal ritual, and an emotional anchor for generations of Hungarians. Families return year after year to swim in its warm sekély víz (shallow water), walk along its mólók (piers), and enjoy lazy afternoons under the sun with lángos (deep-fried flatbread) in one hand and fröccs (wine spritzer) in the other. Whether in the elegant north or the bustling south, the lake represents more than just leisure—it is a mirror reflecting Hungary’s past, present, and dreams of escape.

The northern shore, with its rolling szőlőhegyek (vineyards), quaint falvak (villages), and historic landmarks, offers a more tranquil, cultural experience. Towns like Tihany, famous for its bencés apátság (Benedictine abbey), or Badacsony, known for its volcanic wines and scenic kilátók (lookout points), draw those in search of beauty, heritage, and serenity. Here, the rhythm of life slows, and one can sip a glass of kéknyelű (a rare white wine) while overlooking the calm waters from a vine-covered terrace. The southern shore, in contrast, is defined by wide beaches, party towns, and a youthful energy. Places like Siófok and Balatonlelle are known for their strandélet (beach life), water sports, and vibrant éjszakai élet (nightlife). Children build castles from the lake’s soft iszap (mud), while teenagers crowd the fesztiválok (festivals), and grandparents unwind in gyógyfürdők (thermal spas) nearby.

The lake has always played a vital role in Hungarian identity. During the szocialista korszak (socialist era), when international travel was restricted, Balaton became the vacation destination for all social classes—one of the few places where East met West, especially in the camps and resorts built along its shores. The classic Zimmer Frei signs still evoke memories of youth hostels, homemade plum jam, and long bike rides along the kerékpárút (bike path) that circles the lake. Even today, Balaton continues to evolve. Its culinary scene has been revitalized with gasztrofalvak (gastro-villages), artisanal markets, and borfesztiválok (wine festivals), while preserving its core of authentic Hungarian hospitality.

SZIGET FESTIVAL

The Sziget Fesztivál (Sziget Festival) is one of Hungary’s most iconic and internationally celebrated cultural events—a week-long explosion of music, art, and human connection held each August on Óbudai-sziget (Old Buda Island), a green stretch of land nestled in the Duna (Danube River) in the heart of Budapest. Nicknamed the “Island of Freedom,” Sziget draws hundreds of thousands of visitors from across the globe, transforming the island into a temporary republic of creativity, diversity, and shared euphoria. What began in 1993 as a modest gathering of alternative music lovers and university students, then called Diáksziget (Student Island), has grown into one of Europe’s largest and most influential multi-genre music festivals. It is now a sprawling temporary city, complete with dozens of stages, immersive art installations, themed villages, wellness areas, and cultural programs that go far beyond music.

Each year, Sziget hosts an eclectic lineup of global superstars, underground legends, and experimental performers across genres, from rockzene (rock music) and elektronikus zene (electronic music) to világzene (world music), hiphop, jazz, and more. Headliners like Ed Sheeran, Florence + The Machine, Måneskin, or David Guetta perform on the Nagyszínpad (Main Stage), where crowds of tens of thousands sing and dance in unison beneath fireworks and LED lights. But Sziget’s magic lies not only in the stars it attracts, but in the unexpected: a cirkuszi sátor (circus tent) hosting aerial performers, a színházi tér (theatre space) for avant-garde drama, or a late-night DJ pult (DJ booth) in the woods pulsing until sunrise. Every corner of the island invites felfedezés (discovery), whether it’s a fire show, a jógaóra (yoga session), a drag performance, or a poetry slam.

What sets Sziget Fesztivál apart from other mega-festivals is its ethos. It is fiercely international, welcoming “Szitizens” (Sziget-goers) from over 100 countries, creating a utopian atmosphere where cultures meet, coexist, and collaborate. The festival is also built on strong values: environmental awareness, freedom of expression, and közösségi szellem (community spirit). Its sustainability efforts include újrahasznosítás (recycling), ökohulladék (eco waste), reusable cup systems, and green transportation solutions. The Love Revolution campaign addresses global issues from climate change to human rights, giving the festival a conscience as well as a heartbeat. Many Szigetlakók (island residents) return year after year, not only for the music but for the shared spirit of openness, equality, and joy.

For many, Sziget is not merely a festival—it is a zarándoklat (pilgrimage), a summer rite of passage, a dreamlike week that lingers in memory long after the last beat fades. On this island, music becomes a language, difference becomes beauty, and the ordinary dissolves into the extraordinary. The Sziget Fesztivál is where Hungary becomes a bridge to the world, and for seven unforgettable days, the world dances back.

GOULASH

Gulyás (goulash) is the culinary soul of Hungary, a dish that has transcended the boundaries of cuisine to become a powerful national symbol, deeply tied to the land, the people, and the shared memory of the puszta (Hungarian plains). At its heart, gulyás is a rich meat stew or soup, traditionally made with marhahús (beef), burgonya (potatoes), sárgarépa (carrots), zeller (celery), and plenty of pirospaprika (sweet paprika), simmered together in a bogrács (cauldron) over an open fire. Its distinctive balance of smokiness, spice, and comfort makes it much more than a rural meal—it is a national treasure, representing Hungary’s historical connection to herding, open-air cooking, and the spirit of independence.

The origins of gulyás go back to the gulyások (cowherds) who roamed the Alföld (Great Hungarian Plain) with their szürkemarha (Hungarian grey cattle), preparing simple, hearty meals with limited resources. These herdsmen developed a method of cooking that was both efficient and flavorful, relying on a cast-iron bogrács, which could be hung over a fire and used to cook large portions of food slowly. The base of the dish was built on hagyma (onion) and zsír (fat), sautéed together before the meat and spices were added. Paprika, introduced in the 18th century, revolutionized the dish, giving it the unmistakable color and flavor now associated with Hungarian cuisine.

Unlike other stews, gulyásleves (goulash soup) maintains a thinner, soup-like consistency, often served with csipetke (small handmade dumplings) added toward the end of cooking. This differentiates it from pörkölt (stew) and paprikás, which are thicker and usually eaten with galuska (spaetzle-style noodles). The inclusion of kömény (caraway seeds), fokhagyma (garlic), and sometimes paradicsom (tomatoes) or zöldpaprika (green peppers) lends further complexity, while the slow simmering process melds flavors into something deeply warming and robust.

Today, gulyás is omnipresent in Hungary. It is served in homes and csárdák (roadside inns), at fesztiválok (festivals) and state events, in street markets and turistalátványosságok (tourist attractions), often cooked in massive bogrács pots that recall its nomadic origins. Beyond its flavor, gulyás represents vendégszeretet (hospitality), as it is almost always prepared for sharing. The act of cooking gulyás together—tending the fire, tasting the broth, adjusting the seasoning—is a communal ritual, whether done by a village, a family, or a group of friends on a hétvégi kirándulás (weekend trip). In this way, the dish transcends the plate, becoming a form of gathering, storytelling, and cultural expression.

To taste a spoonful of gulyás is to step into a historical landscape flavored by migration, herding, and innovation. It is the warmth of the tűzhely (hearth), the smoke of the tábori tűz (campfire), and the legacy of people who created something extraordinary from the simplest of ingredients. It’s not just food—it’s a memory preserved in spice, simmered into a shared Hungarian identity.

UNICUM

Unicum is more than just a drink in Hungary—it is a national symbol, a potent elixir, and a complex embodiment of Hungarian taste, tradition, and identity. This dark, bitter gyomorkeserű (digestive bitter) has been produced since 1790, originally developed as a medicinal tonic by Dr. Zwack, the royal physician to Emperor II. József (Joseph II). Legend has it that after tasting the concoction, the emperor declared, “Das ist ein Unikum!” (That is a unique one!), thus giving the drink its distinctive name. The recipe was passed down within the Zwack család (Zwack family), remaining a closely guarded secret made from more than fűszerek és gyógynövények (40 herbs and spices), aged in tölgyfa hordók (oak barrels) for months beneath the family’s distillery in Budapest. This process gives Unicum its iconic depth—a fusion of earthy bitterness, medicinal intensity, and aromatic warmth that lingers long after the first sip.

While Unicum began as a gyógyszer (medicine), its transition to a commercial likőr (liqueur) marked its integration into Hungarian social life. During the Monarchia ideje (Austro-Hungarian Empire period), it became a fashionable aperitif among the bourgeoisie, enjoyed in cafés, restaurants, and grand homes. Even under szocializmus (socialism), when many traditional products were suppressed or standardized, Unicum survived—though the Zwack family was forced into exile and the state took control of the production. However, after the political transition of 1989, the Zwack örökösök (Zwack heirs) returned and regained ownership, restoring the brand’s integrity and returning to the original recipe.

Today, Unicum is omnipresent in Hungarian drinking culture. It is served szobahőmérsékleten (at room temperature), in small, rounded poharak (glasses), often before or after a heavy meal to aid digestion. In traditional vendéglők (taverns), modern kocsmák (pubs), or elegant borbárok (wine bars), a glass of Unicum carries connotations of both heritage and masculinity. There are several versions now, including Unicum Szilva (Plum Unicum), aged with dried plums for a fruitier note, and seasonal or limited-edition releases that celebrate Hungarian holidays or historical events. The signature round üveg (bottle), marked with a red kereszt (cross) on a green background, is instantly recognizable and often given as a szuvenír (souvenir) or proudly displayed on home shelves.

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Hungarian, we recommend that you download the Complete Hungarian Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't find in any other textbook so you can amaze your Hungarian friends thanks to your knowledge of their country and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get hours of Podcasts to Practice your Hungarian listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Hungarian today!